Through a friend (Thanks, A!), I recently discovered GiveWell, an independent, nonprofit charity evaluator. GiveWell reviews information about charities and rates them based on how effective they are at solving the problems they claim to address in the world, how efficiently they use donor funds to achieve their goals, how they track their own successes and failures over time, and how transparent the whole process is. This information is posted in detail on their website so that people who are considering charitable giving can review before deciding where to give.

Most prospective donors make decisions about where to give their money based on their own personal feelings and interests. For example, if I feel strongly about the AIDS crisis in Africa, I will donate heavily to organizations who claim to be doing something about it. If I am or know a cancer survivor or victim, I might choose to donate to a group aiming to find a cure. Others may feel strongly about environmental issues such as clean water and air, global climate change, etc. Once we have made the decision to donate, most people look no further than the organization’s own website or printed materials to make our final decision. The folks behind GiveWell knew or suspected that many—if not most—charity organizations overstate their effectiveness, and this causes donor dollars to go down a black hole rather than getting to people who could actually make good use of the funds.

There is so much interesting information on the site, I can’t go into it all here. But I did want to touch on just one issue as an example, and that is water issues. Last summer I was reading Paul Theroux’s Dark Star Safari, his account of a personal overland journey from Cairo to Cape Town. Traveling through Africa, he came across a large number of aid workers purporting to be helping the African people in a number of ways, but he became convinced over time that they were having no effect or a negative effect on the people. This was a viewpoint I had never encountered before, being someone who is not too cynical and therefore assumed that most ‘aid’ organizations were effectively ‘aiding’ the people they said they were. Since reading Theroux’s book, I’ve come across similar arguments in other readings.

One of the examples I remember from the book were the large number of broken-down, useless water wells he came across in his travels. When asking the local people about the wells, he was told that the well had been put in by an aid organization and had worked for a few years, but when it broke down, no one was trained to fix it so the people went back to getting water from other sources. Based on GiveWell’s analysis, there are hundreds if not thousands of defunct wells in Africa right now. Only one aid organization they have located (and they really looked!) actually keeps information about the status of the wells after they have been dug. Another issue: sometimes wells are dug in places that are completely inconvenient to the people living there. If a person can get clean-looking water from a nearby source, they would not walk twice as far to get water from the new well. So…there are also a number of wells that no one has ever really used.

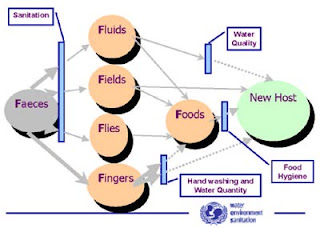

It’s not just a question of abandoned wells, however. You have to consider what it is that these wells are supposed to accomplish. Why did we decide the people needed a well in the first place? The answer, of course, is that clean drinking water reduces the spread of disease. Unfortunately, water is only one of the ways that disease is spread and not necessarily the main one. Take a look at the diagram below:

If our aim is to reduce the spread of diseases in Africa, we have to consider that providing new water wells all over the place is not necessarily the most effective way to address the problem, even if it does sound good to donors and makes for a great photo op. What if there are more effective ways to limit the spread of disease? What if we took all the money people are donating to build wells and put it towards this solution instead? Could the funds stretch farther and the solutions reach more people? Would it be more sustainable over time?

I don’t claim to have an answer to this problem. I’m certainly not saying, “Don’t donate.” But I agree with the folks at GiveWell who suggest that we should put our money primarily into projects that can report some quantifiable positive result, not just anecdotes.

*For GiveWell's full analysis of water charities (interesting and readable, I promise), click here.

*For a list of charities highly rated by GiveWell, click here.

*For GiveWell's take on donations toward Japan earthquake/tsunami relief (interesting!), click here.

No comments:

Post a Comment